点击上方 国际母乳会LLL 设为星标 ,获取哺乳信息

从宝宝出生后最初的相处开始,母乳喂养往往成为亲子关系中非常重要又舒适的一部分。除了持续提供重要的营养素以及保护身体免受疾病侵害之外,它也是继续保持母婴联结、安抚发育中婴儿的绝佳方法,白天如此,夜晚亦如是。事实上,夜间哺乳在生物学上是一种常态行为。

然而,随着时间的推移,宝宝长牙了,一个新问题可能会出现。牙医可能告诉您,母乳喂养会导致蛀牙,一些牙医可能建议您早点断奶,或至少不要在夜间喂奶。

本文我们将探讨有关牙齿健康的问题和担心,并讨论如何在您和宝宝继续享受重要的哺乳关系的同时保护牙齿的健康。

母乳中的常见疑惑

·母乳喂养真的会导致孩子蛀牙吗?

·研究是否表明,孩子应该在一岁后断奶来预防蛀牙?

·饮食是如何影响牙齿健康的?

·该怎样确保孩子良好的口腔卫生?

·如果牙医建议停止母乳喂养,怎么办?

·有研究表明母乳可以抵抗细菌吗?

·哪些孩子更容易患蛀牙?

·这些信息能给予妈妈哪些帮助?

母乳喂养真的会导致孩子蛀牙吗?

研究表明,母乳喂养的孩子比配方奶喂养的孩子患蛀牙(龋齿)的可能性要小得多。

根据世界卫生组织(WHO)在2020年1月发布的一份报告,“证据表明,在出生第一年母乳喂养的婴儿,龋齿的发生率要低于配方奶喂养的婴儿。”

该报告补充说: “一项系统综述表明,当母乳喂养超过一岁时,患儿童早期龋齿的风险较高,但数据分析没有充分对照重要的混杂因素,例如从其它来源摄入的糖分。”

母乳喂养不仅对母亲和孩子的健康有持续的重要性,也促进了下颌和牙齿的最佳发育。母乳喂养的孩子患牙齿畸形(错牙合)的可能性较小,而且母乳喂养的时间越长,风险就越低。母乳喂养的婴儿也得到了保护以免患氟斑牙(牙齿变色)。

研究是否表明,孩子应该在一岁后断奶来预防蛀牙?

没有令人信服的证据表明是母乳喂养本身导致了问题,或停止母乳喂养就能预防蛀牙。研究通常着眼于乳糖 (存在于母乳中的一种糖) 对牙齿的影响,而不是母乳具有抗菌性、有益的酶和较高pH值的整体影响。

有关一岁后母乳喂养对牙齿健康影响的研究确认,在观察儿童早期龋齿时,很难充分对照其它因素,如饮食、牙齿卫生和口腔中存在的细菌。

2018年12月,英格兰公共卫生署表示,没有高质量的研究证实牙齿损害与母乳喂养到12个月以上之间存在关联。其指南还强调了不母乳喂养的风险。

其它报告也认同研究可能未考虑在母乳喂养时摄入的饮食。2019年一篇题为《母乳喂养与儿童早期龋齿:文献回顾、建议和预防》的综述表明,异质性研究的结果“往往不考虑矛盾因素,如母亲或婴儿的饮食习惯(夜间哺乳、每天进食的次数、吃甜食等) 、牙齿卫生或社会文化背景。”

2019年,另一份题为《改变儿童早期患龋齿的风险因素相关证据的系统综述》的报告对72个月以下儿童的母乳喂养和儿童期龋齿进行了研究。它总结说,母乳喂养到24个月并没有增加儿童早期龋齿的风险,尽管有一些“低质量”的证据显示较长时间的母乳喂养会增加患龋齿的风险。这篇综述补充说,一些数据表明辅食中的糖分造成了风险的增加。

2007年的一项旧的美国研究《美国婴儿母乳喂养与儿童早期龋齿之间的关系》,评估了1,576名2-5岁儿童龋齿的潜在风险因素,并证实没有证据表明母乳喂养或其持续时长是儿童早期龋齿、严重的儿童早期龋齿、或乳牙龋齿和充填牙面的风险因素。

饮食是如何影响牙齿健康的?

目前的研究表明尚不能排除导致牙齿问题的原因之一是我们的现代饮食,而不是母乳喂养。如今的饮食包括许多易引起蛀牙的食物,而且很难完全不让孩子沾一点儿糖分。

变形链球菌是一种口腔细菌,在糖分存在的情况下对牙釉质伤害特别大。婴儿可以从携带此菌株的成人那里,在与他们分享食物、共用餐具或用嘴亲吻时被感染上; 因此,重要的事情是主要照护婴儿的人也要保持良好的口腔健康。尽管牙医可能会建议您断夜奶来预防婴儿或学步儿长蛀牙,但上述的那些因素更可能影响到孩子的牙齿健康,从而使断夜奶来解决蛀牙这一方法显得如此无关紧要。

加利福尼亚大学2014年的一项研究强调了要考虑母乳喂养婴儿的整体饮食的重要性,《用边际结构模型估测长期母乳喂养与龋齿的相关性》这篇文章研究了长期母乳喂养与龋齿的风险之间可能的联系。

虽然研究发现证据表明,母亲在孩子两岁后白天母乳喂养得越频繁,早期严重龋齿的风险就越大,但作者本杰明·查菲仍对母乳喂养做出了积极评价,他说这项研究并未表明母乳喂养会导致龋齿,哺乳妈妈首先要做的应该是确保婴儿获得最佳的营养。

作者推测,母乳加上现代食品中过量的精制糖可能会导致那些哺乳时间最长、次数最多的婴儿出现蛀牙的情况更严重。这项研究还讨论了“瓶喂母乳”和亲喂母乳的区别,并强调了近一半的儿童在六个月前进行过婴儿配方奶粉喂养。

2020年澳大利亚的一项研究也通过调查学龄前儿童的母乳喂养方式和饮食中游离糖的摄入量来观察他们的饮食和牙齿健康。作者的结论是: “母乳喂养的做法与儿童早期龋齿没有关联性。鉴于母乳喂养的众多益处,以及本研究中和澳大利亚总体的长期母乳喂养率都较低,限制母乳喂养的建议是没有根据的,母乳喂养应根据全球和各国的建议加以推广。为了减少儿童早期龋齿的发生率,我们需要做更多努力来限制游离糖含量高的食物。”

该怎样确保孩子良好的口腔卫生?

研究母乳喂养和牙齿健康得出的压倒性结论是,牙齿和口腔卫生与饮食一同对预防蛀牙至关重要。

2019年题为《改变儿童早期龋齿的风险因素相关证据的系统综述》的报告得出结论: “提供氟化水并教育照护人是预防儿童早期龋齿的合理方法。限制配方奶和辅食中的糖分应是此教育的一部分。”

2014年的研究《用边际结构模型估测长期母乳喂养与龋齿的相关性》的作者查菲说,他的研究团队收集了刷牙习惯的数据,但没有调查最后一次喂养后清洁牙齿与龋齿之间的具体联系。他补充说,任何从口腔中去除碳水化合物和糖分的东西都有助于防止蛀牙。

一项经常被引用的2015年的研究《母乳喂养与龋齿的风险: 系统综述和荟萃分析》评论说:“很少有研究同时评估母乳喂养、奶瓶喂养和非奶瓶喂养或非母乳喂养的12个月以上儿童的龋齿风险。”它还得出结论,当婴儿不再纯母乳喂养或配方奶喂养时,需要考虑饮食和刷牙习惯等混杂因素。作者指出,“需要进一步的研究,仔细对照相关的混杂因素,以阐明这个问题,并更好地指导婴儿喂养指南的制定。”

英格兰公共卫生署建议,父母或照护人应该这样给孩子刷牙:

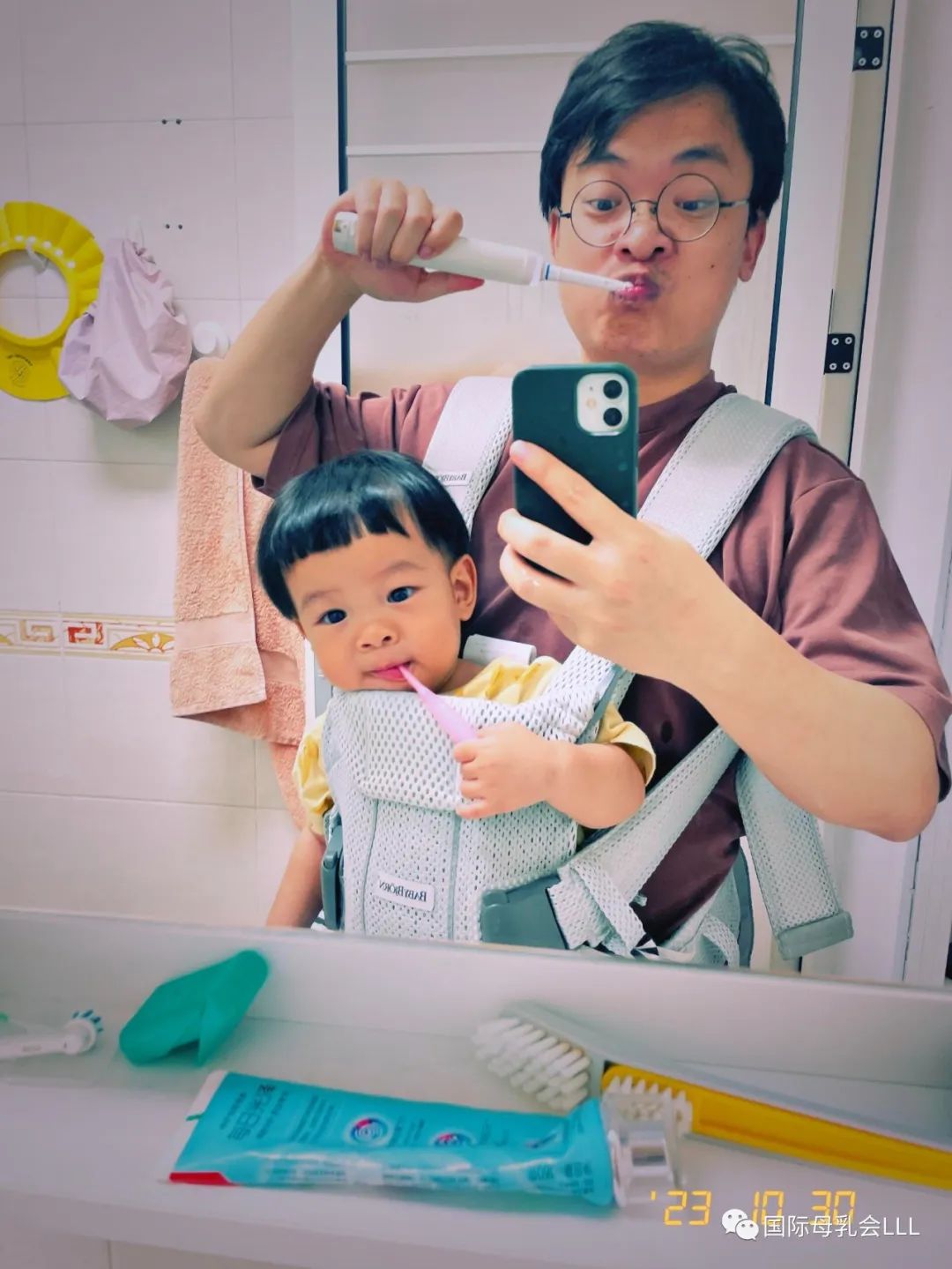

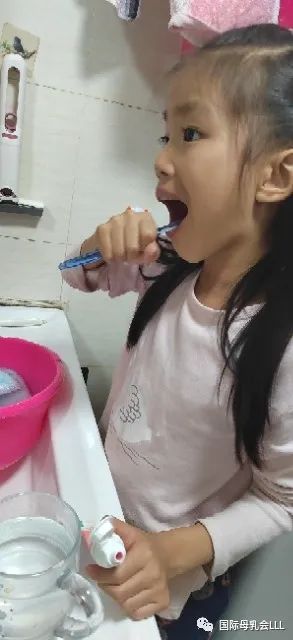

一旦长牙就开始

每天两次

两次刷牙时间:白天一次,晚上(或临睡前)一次

使用含氟量至少1000 ppm的牙膏

只挤一点儿牙膏

人们似乎普遍认为,帮助孩子保持牙齿健康的最好方法是每天用含氟牙膏彻底刷牙至少两次。鼓励婴儿吃完辅食后用水漱口、或者至少喝点水也会有帮助。

一些牙医建议每次哺乳后(包括夜里)都给孩子擦拭牙齿,但这可能证明是一个困难且不必要的流程。

虽然没有必要不给孩子喂夜奶,但是睡觉前刷牙、之后不给吃任何碳水化合物很重要。这与1999年的一项研究结果一致,该研究调查了将拔出的健康牙齿浸泡在不同溶液中对牙齿健康的影响。结果表明,母乳本身几乎与水相同,不会引起蛀牙。然而,当少量糖加入到母乳中时,这种混合物会比糖水更严重地引起蛀牙。

您可能还想咨询牙医使用木糖醇的有关信息。它是一种天然的代糖,可以干扰细菌粘附在牙齿表面的能力。除了可以作为烹饪原料外,木糖醇也经常用于口香糖中,携带大量变形链球菌的母亲使用木糖醇可能会降低她们口腔中的细菌数量,从而降低把变形链球菌传染给婴儿的风险。

总之,母乳喂养配合上刷牙,并通过少吃含糖食物来改善营养,会继续显著地促进很多母亲和婴儿的健康。建议定期检查牙齿,并向牙医咨询有关饮食习惯(特别是糖摄入量)、口腔卫生或补充氟化物的预防建议。

如果牙医建议停止母乳喂养,怎么办?

牙医自然很关心口腔健康,但他们可能没有接受过太多培训来全面了解母乳喂养对母亲和儿童的短期和长期身心健康的重要性。

根据2018年英格兰公共卫生署对母乳喂养和牙齿健康的指导,“与其它行为相比较,母乳喂养是一种生理常态;因此,牙科团队应该促进母乳喂养,并在其咨询建议中加上不母乳喂养对全身和口腔健康的风险。”该指导指出,牙医及其团队应支持来自世卫组织和英国政府的循证指南,并在给牙科团队和医疗保健专业人员提供的核心信息中包括以下建议:

世界卫生组织建议婴儿在出生后的头六个月纯母乳喂养,以达到最佳的生长、发育和健康状况,然后继续母乳喂养至两岁或以上,同时补充辅食。

当用其它灵长类动物的进化与人类进行比较时,有趣的是注意到了人类婴儿的母乳喂养有望持续至少两年半。人类学家凯西 · 德特威勒指出,虽然“从统计学上讲,全世界平均的断奶年龄是没有意义的”,但人类学家发现,儿童自然离乳的年龄在两岁半到七岁左右。

由于对蛀牙未经证实的恐惧,在您和宝宝准备好之前就断奶,将会否定你们两人从持续母乳喂养中获得的许多积极成果,并且可能导致不必要的奶瓶介入。

以上讨论的研究表明,没有必要为了保护孩子的牙齿健康而戒掉夜奶。采取良好的口腔卫生方案、使用含氟牙膏以及食用低糖饮食就可能对降低儿童早期龋齿风险产生更显著的影响。

如果大家有关于母乳喂养和口腔清洁的其他问题,可以在文章下面留言,我们在日后可以访谈牙医母乳妈妈,为大家准备相关的问答小贴士~

Breastfeeding and Dental Health

From the early days with your newborn, breastfeeding often becomes a very important and comfortable part of your relationship with your child. As well as continuing to provide important nutrients and protection against ill health, it’s a wonderful way to continue to connect with and comfort your growing infant, both during the day and quite often at night too.In fact, night nursing is a biologically normal behaviour.

However, as time goes by and your baby’s teeth come in, a new concern may emerge. You may be told by your dentist that breastfeeding causes tooth decay and some dentists may advise early weaning from the breast, or at least no night-time nursing.

In this article we look at questions and concerns about dental health and discuss how it can be protected while you and your baby continue to enjoy your important breastfeeding relationship.

Is it true that breastfeeding will contribute to my child’s tooth decay?

Does the research show I should wean after one to prevent tooth decay?

How does diet affect dental health?

How can I ensure good dental hygiene?

What if my dentist tells me I should stop breastfeeding?

Do studies show human milk may protect against bacteria?

Are some children more susceptible to dental caries?

What can I take from all this information?

Is it true that breastfeeding will contribute to my child’s tooth decay?

Studies show that a breastfed child is significantly less likely to suffer from tooth decay (dental caries) than a child who is formula fed. According to a report issued by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in January 2020, “Evidence suggests that infants who are breastfed in the first year of life have lower levels of dental caries than those fed infant formula.”

The report adds:“One systematic review suggested a higher risk of ECC [early childhood caries] when breastfeeding extends beyond one year of age, but the data analysis did not control adequately for important confounders such as intake of sugars from other sources.”

As well as the continuing significance to the health of mother and child, breastfeeding promotes optimal jaw and tooth development. A breastfed child is less likely to suffer from crooked teeth (malocclusion)and the longer the child is breastfed the greater the reduction in risk. A breastfed baby may also be protected from developing dental fluorosis (discolouration of teeth).

Does the research show I should wean after one to prevent tooth decay?

There is no convincing evidence to show that breastfeeding itself is causing problems or that stopping will prevent tooth decay. Studies often look at the effects of lactose (milk sugar, which is also present in breastmilk) on teeth, not the effects of breastmilk as a whole, with its antibacterial properties, helpful enzymes and high pH.

Research about the impact of breastfeeding on dental health after the age of one acknowledges that it is difficult to adequately control other factors such as diet, dental hygiene, and the presence of bacteria in the mouth, when looking atearly childhood caries.

In December 2018, Public Health England said that there are no good quality studies proving links between dental damage and breastfeeding beyond 12 months. Their guidance also emphasizes the risks of not breastfeeding.

Other reports agree that research may not take into account diet alongside breastfeeding. A 2019 review entitled ‘Breastfeeding and early childhood caries. Review of the literature, recommendations, and prevention’ states that results from heterogeneous studies “do not always take into account contradictory factors such as eating habits of the mother or infant (feeding during the night, number of meals per day, eating sweet foods etc.), dental hygiene, or the sociocultural context.”

Another 2019 report entitled ‘Systematic Review of Evidence Pertaining to Factors That Modify Risk of Early Childhood Caries’looked at breastfeeding and childhood caries in children aged up to 72 months. It concluded that breastfeeding for up to 24 months did not increase early childhood caries risk, although there was some “low-quality” evidence for increased risk in longer duration breastfeeding. The review added that some data indicated the impact of sugars in complementary foods increased risk.

An older US study from 2007, ‘Association between infant breastfeeding and early childhood caries in the United States’,assessed the potential risk factors for dental caries in 1,576 children aged 2-5 years old and demonstrated that there is no evidence to suggest that breastfeeding or its duration are risk factors for early childhood caries, severe early childhood caries, or decayed and filled surfaces on primary teeth.

How does diet affect dental health?

Current studies indicate that research cannot rule out our modern diet as a cause of dental problems rather than breastfeeding. Today’s diet includes many more cavity-inducing foods and it can be hard to get all those sugars off your child’s teeth.

Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) is an oral bacterium that’s especially hard on tooth enamel in the presence of sugar. Babies can pick up S. mutans from adults who carry the strain and who share food, utensils or mouth kisses with them; therefore it is important that the primary caregiver of a baby also maintains good oral health.

Although your dentist may advise you to stop breastfeeding at night to prevent your baby or toddler from developing cavities, these factors are much more likely to play a role in your child’s dental health, making night weaning an irrelevant solution to the problem.

The importance of taking into account the overall diet of a breastfed infant is highlighted in a 2014 study from the University of California, ‘Association of long-duration breastfeeding and dental caries estimated with marginal structural models’, looking at possible links between longer-term breastfeeding and the risk of tooth decay and cavities.

Although the research found evidence of a greater risk of severe early tooth decay the more frequently a mother breastfed her child beyond the age of 24 months during the day, the author, Benjamin Chaffee, made positive comments about breastfeeding saying that the study does not suggest that breastfeeding causes caries and that the Number 1 priority for breastfeeding mothers should be ensuring their babies’ optimal nutrition.

The authors speculated that it is possible that breastmilk in conjunction with excess refined sugar in modern foods may be contributing to the greater tooth decay seen in babies breastfed the longest and most often. This study also talks about “breastmilk bottles” as opposed to breastfeeds and highlights that nearly half the children had also been given infant formula by six months.

A 2020 Australian studyalso looked at diet and dental health in pre-schoolers by studying breastfeeding patterns and the intake of free sugars in their diet. The authors concluded that “Breastfeeding practices were not associated with early childhood caries.

Given the wide-ranging benefits of breastfeeding, and the low prevalence of sustained breastfeeding in this study and Australia in general, recommendations to limit breastfeeding are unwarranted, and breastfeeding should be promoted in line with global and national recommendations. To reduce the prevalence of early childhood caries, improved efforts are needed to limit foods high in free sugars.”

How can I ensure good dental hygiene?

The overwhelming conclusion when looking at breastfeeding and dental health is that, alongside diet, dental and oral hygiene is crucial in preventing cavities.

The 2019 report entitled ‘Systematic Review of Evidence Pertaining to Factors That Modify Risk of Early Childhood Caries’concluded that “Providing access to fluoridated water and educating caregivers are justified approaches to ECC prevention. Limiting sugars in bottles and complementary foods should be part of this education.”

Chaffee, the author of the 2014 study ‘Association of long-duration breastfeeding and dental caries estimated with marginal structural models’said his team of researchers collected data on tooth brushing habits, but did not investigate a specific link between cleaning teeth after the last feeding and caries. He added that anything that removes carbohydrates and sugars from the oral cavity should help prevent tooth decay.

An often-quoted 2015 study ‘Breastfeeding and the risk of dental caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis’ commented that “There was a lack of studies on children aged >12 months simultaneously assessing caries risk in breastfed, bottle-fed and children not bottle or breastfed.”

It also concluded that when infants were no longer exclusively breastfed or formula fed, confounding factors such as diet and tooth brushing practices needed to be taken into account. The authors stated that “further research with careful control of pertinent confounding factors is needed to elucidate this issue and better inform infant feeding guidelines.”

Public Health England’s recommendations are that parents or carers should brush their children’s teeth:

·as soon as they erupt;

·twice a day;

·last thing at night (or before bedtime) and on one other occasion;

·with a toothpaste containing at least 1000 ppm fluoride;

·using only a smear of toothpaste.

There seems to be general agreement that the best way to aid your child’s dental health is to brush their teeth thoroughly at least twice a day with fluoridated toothpaste. It might also help to encourage your baby to swish with, or at least sip, water after eating solid foods. Some dentists recommend wiping a child’s teeth after each nursing, including during the night, but this can prove to be a difficult and unnecessary procedure.

While there is no need to keep your child from nursing at night, it is important to brush teeth before going to sleep and not to offer any carbohydrates after that. This is in line with the findings of a 1999 study which investigated the effect of different solutions on dental health by immersing healthy, extracted teeth in them. The results showed that breastmilk alone was practically identical to water and did not cause tooth decay. However, when a small amount of sugar was added to the breastmilk, the mixture was worse than a sugar solution when it came to causing tooth decay.

You may also want to ask your dentist for information about using xylitol. This is a natural carbohydrate sugar substitute that interferes with bacteria’s ability to stick to the tooth surface. Aside from being available as a cooking ingredient, xylitol is often found in chewing gum and it’s possible that its use by mothers with high levels of S.Mutans may reduce the level of bacteria in their mouths, consequently lowering the risk of passing S.Mutans to their baby.

In summary, breastfeeding, when accompanied by toothbrushing and better nutrition by reducing the frequency and consumption of sugary foods, continues to contribute significantly to well-being for many mothers and infants. Regular consultation with a dentist for examination and preventive advice regarding dietary practices (especially sugar intake), oral hygiene, or supplementary fluoride is recommended.

What if my dentist tells me I should stop breastfeeding?

While dentists are naturally concerned about oral health, they may not have a lot of training on the overall significance of breastfeeding to the short- and long-term physical and mental health of both mother and child.

According to the 2018 Public Health England guidance on Breastfeeding and dental health, “Breastfeeding is the physiological norm against which other behaviors are compared; therefore, dental teams should promote breastfeeding and include in their advice the risks of not breastfeeding to general and oral health.”

The guidance states that dentists and their teams should support evidence-based guidelines from the WHO and the UK government and in a core message to dental teams and healthcare professionals includes the following recommendations:

·“Dental teams should continue to support and encourage mothers to breastfeed.”

·“Not being breastfed is associated with an increased risk of infectious morbidity (for example gastroenteritis, respiratory infections, middle-ear infections).”

·“Breastfeeding up to 12 months of age is associated with a decreased risk of tooth decay.”

If your dentist would like further advice, the UKHSA refers them to ‘Health Matters: Child Dental Health’ (2017)and ‘Delivering Better Oral Health: An Evidence-Based Toolkit for Prevention’ (2014).

There are supportive dentists who understand the significance of breastfeeding so if you are under pressure to wean, try to find one who respects your choices.

Do studies show human milk may protect against bacteria?

The late Dr. Brian Palmer, DDS studied children’s skulls that were thousands of years old and he found almost no cavities. In his presentations, he referred to evidence from anthropologists and commented that “If breastmilk caused decay – evolution would have selected against it. It would be evolutionary suicide for breastmilk to cause decay.”

One reason for the lack of cavities identified by Dr. Palmer may be that the mechanics of breastfeeding make it unlikely for human milk to stay in the baby’s mouth for long. During breastfeeding, the nipple is drawn deep within the baby’s mouth, and milk is literally squirted into the back of it.

The nursing child must swallow before he can go on to the next step of the suckling process. In contrast, baby bottles can drip milk, juice, or formula into the baby’s mouth even if he is not actively sucking. If the baby does not swallow, the liquid can pool in the front of the mouth around the teeth. The artificial nipple is very short, so the liquid in the bottle is likely to pass over teeth before being swallowed.

Another reason is that bacteria which cause cavity formations are inhibited by several components of human milk including high pH levels. IgA and IgG have the potential to retard streptococcal growth, and S. mutans is highly susceptible to the bactericidal action of lactoferrin, an active component of human milk.Human milk also actively strengthens teeth by depositing calcium and phosphorus on them.

Dr. Palmer was of the opinion that dry mouth is another factor that can increase the incidence of early childhood caries. Saliva, which helps maintain normal pH, is not produced as much at night, especially among those who breathe through their mouths. An infant or toddler who nurses often at night continues to produce saliva, which may help combat dry mouth.

Are some children more susceptible to dental caries?

In a survey entitled ‘Prolonged, on-demand Breastfeeding and Dental Caries – An Investigation’,Dr. Harry Torney found that four factors were significantly associated with the high caries group. The most significant relationship was with defective enamel while the other three factors related to events that had occurred while the child was in utero.

One of these was maternal stress and/or bereavement as reported by the mother. Another was a reduced intake of dairy products as estimated retrospectively by the mother. The third factor was medically diagnosed illness in the mother.

If a mother’s pre-natal diet and/or antibiotics received during pregnancy have affected the quality of a child’s tooth enamel and resistance to cavities, the permanent teeth are almost always fine. Diet and oral hygiene are also factors, as confirmed by the more recent research discussed above.

Dr. Torney found no correlation between the onset of dental caries under two years of age and breastfeeding patterns such as feeding to sleep, frequent night feeds, etc. In his opinion, under normal circumstances, the antibodies in breastmilk counteract the mouth bacteria which cause tooth decay.

However, in the presence of small enamel defects, the teeth become more vulnerable, and the protective effect of breastmilk is not sufficient to counteract bacteria combined with the sugars in the milk.

According to this research, a baby who is exclusively breastfed (no supplemental bottles, juice, or solids) will not have decay unless he is genetically predisposed, i.e. soft or no enamel. In a baby who does have a genetic problem, weaning will not slow down the rate of decay and may speed it up due to lack of lactoferrin.

Dr. Palmer’s research is in line with this: “Human milk alone does not cause dental caries.

Infants exclusively breastfed are not immune to decay due to other factors that impact the infant’s risk for tooth decay. Decay causing bacteria (streptococcus mutans) is transmitted to the infant by way of parents, caregivers, and others.

A couple of studies have also highlighted a possible association between early childhood caries and maternal Vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy.

What can I take from all this information?

While you may initially feel concerned about the effects of longer-term and nighttime breastfeeding, it is important to look at all the factors contributing to the dental health of your breastfed child.

Historically children who nursed all night had little or no decay until the advent of decay-inducing foods.

Human milk alone rarely contributes to decay and actually has tooth-strengthening properties.

While parents need to be aware of the dangers of sweet foods and drinks and of the benefits of strict oral hygiene and visits to the dentist, it’s important not to overlook the impact on physical and emotional health of breastfeeding for the baby, family and society as a whole.

The WHO recommends that infants be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life to achieve optimal growth, development and health and then continue breastfeeding for up to two years of age and beyond, alongside complementary foods.

When using the evolution of other primates as a comparison point for humans, it is interesting to notice that in human babies breastfeeding would be expected to continue for at least two and a half years.

Anthropologist Kathy Dettwyler states that while“it is meaningless, statistically, to speak of an average age of weaning world- wide” anthropologists have found that children naturally wean between two and a half years and around seven years of age.

Weaning from the breast before you and your baby are ready because of unsubstantiated fears of tooth decay would be denying both of you of the many positive outcomes from continued breastfeeding and may lead to the unnecessary introduction of bottles.

The research discussed above shows that there is no need to night wean your child to take care of their dental health. Adopting a good oral hygiene regimen, using fluoridated toothpaste and consuming a low-sugar diet are likely to have a much more significant impact in terms of reducing the risk ofearly childhood caries.

作者: 安娜伯比奇,国际母乳会英国分会

2022年7月

资料来源:

https://www.laleche.org.uk/breastfeeding-dental-health/

其他网上信息:

https://breastfeeding.support/breastfeeding-and-tooth-decay/

https://kellymom.com/ages/older-infant/tooth-decay/

https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/phe-statement-breastfeeding-and-dental-health/breast-feeding-and-tooth-decay-infographic/

reference resources

参考资源

1.https://www.laleche.org.uk/breastfeeding-beyond-a-year/

2.https://www.laleche.org.uk/reasons-night-waking-biological-norm/

3. World Health Organization. Ending Childhood Dental Caries: WHO Implementation Manual, .https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ending-childhood-dental-caries-who-implementation-manual (accessed 2nd July 2022).

4. Ibidem

5. Abate, A. et al. Relationship between Breastfeeding and Malocclusion: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Nutrients, 2020; 12 (12): 3688. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7761290/ (accessed 2nd July 2022).

6. Brothwell, D. and Limeback, H. Breastfeeding is protective against dental fluorosis in a nonfluoridated rural area of Ontario, Canada. J Jum Lact, 2003; 19 (4): 386-90. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14620452 (accessed on 2nd July 2022).

7. Public Health England. Breastfeeding and dental health, 2018 (updated January 2019). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/breastfeeding-and-dental-health (accessed 2nd July 2022).

8. Branger, B. et al. Breastfeeding and early childhood caries. Review of the literature, recommendations, and prevention. Arch Pediatr, 2019; 26 (8):497-503. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31685411/(accessed 2nd July 2022).

9. Moynihan, P. et al. Systematic Review of Evidence Pertaining to Factors That Modify Risk of Early Childhood Caries. JDR Clin Trans Res, 2019; 4 (3): 202–16. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30931717/ (accessed 2d July 2022).

10. Iida, H. et al. Association Between Infant Breastfeeding and Early Childhood Caries in the United States. Pediatrics, 2007; 120(4): e944-52. Available at https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article-abstract/120/4/e944/71236/Association-Between-Infant-Breastfeeding-and-Early?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed 2nd July 2022).

11. La Leche League International: “The Womanly Art of Breastfeeding”, 2010 edition: Page 242 http://www.lllgbbooks.co.uk/store/p91/The_Womanly_Art_of_Breastfeeding.html

12. Chaffee, B.W. et al. Association of long-duration breastfeeding and dental caries estimated with marginal structural models. Annals of Epidemiology, 2014; 24 (6):448–454. Available at http://www.annalsofepidemiology.org/article/S1047-2797(14)00064-7/abstract (accessed 2nd July 2022)

13. Devenish, G. et al. Early childhood feeding practices and dental caries among Australian preschoolers. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2020; 111 (4): 821–828. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32047898/ (accessed 2nd July 2022).

14.Ibidem

15. Moynihan, P. et al. Systematic Review of Evidence Pertaining to Factors That Modify Risk of Early Childhood Caries. JDR Clin Trans Res, 2019; 4 (3): 202–16. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30931717/ (accessed 2d July 2022).

16. Ibidem

17. Chaffee, B.W. et al. Association of long-duration breastfeeding and dental caries estimated with marginal structural models. Annals of Epidemiology, 2014; 24 (6):448–454. Available at http://www.annalsofepidemiology.org/article/S1047-2797(14)00064-7/abstract (accessed 2nd July 2022)

18.Tham, R. et al. Breastfeeding and the risk of dental caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr, 2015; 104 (467): 62–84. Available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/apa.13118(accessed 2nd July 2022).

19. Ibidem

20. Erickson, P.R. and Mazhari, E. Investigation of the role of human breast milk in caries development. Pediatr Dent, 1999; 21 (2): 86-90. Available at https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/publications/archives/erickson-21-02.pdf (accessed 2nd July 2022).

21. Isokangas, P. et al. Occurrence of dental decay in children after maternal consumption of xylitol chewing gum, a follow-up from 0 to 5 years of age. J Dent res, 2000; 79 (11): 1885-9. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11145360/ (accessed 2nd July 2022).

22.Public Health England. Breastfeeding and dental health, 2018 (updated January 2019). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/breastfeeding-and-dental-health (accessed 2nd July 2022).

23.Public Health England. Health matters: child dental health, 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-child-dental-health/health-matters-child-dental-health (accessed 2nd July 2022).

24.Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention, 2014.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention (accessed 2nd July 2022).

25.Brian Palmer, DDS: “Infant Dental Decay: Is it related to Breastfeeding?” Available at http://www.brianpalmerdds.com/pdf/caries.pdf (accessed 2nd July 2022)

26.Slavkin, H.C. Streptococcus mutans, early childhood caries and new opportunities, J Am Dent Assoc, 1999; 130 (12): 1787-92. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10599184 (accessed 2nd July 2022).

27.Torney, H. Prolonged, On-Demand Breastfeeding and Dental Caries-An Investigation. [Unpublished MDS thesis] Dublin, Ireland, 1992.

28.Ibidem

29.Brian Palmer, DDS: “Infant Dental Decay: Is it related to Breastfeeding?” Available at http://www.brianpalmerdds.com/pdf/caries.pdf (accessed 2nd July 2022)

30.Schroth, R. J. Influence of Maternal Prenatal Vitamin D Status on Infant Oral Health. University of Manitoba. 2010. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/1993/4274 (accessed 2nd July 2022).

31.Singleton, R. et al. Association of Maternal Vitamin D Deficiency with Early Childhood Caries. J Dent Res, 2019; 98 (5): 549-555. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6995990/ (accessed 2nd July 2022).

32.Dettwyler, K., PhD. A Natural Age of Weaning, http://www.whale.to/a/dettwyler.html (accessed 2nd July 2022).

END

译者 | Lynn

审阅 | 传艳、张楠、笑仪、Victoria

编辑 | 李热爱

更多阅读资料,

欢迎大家访问“国际母乳会LLL”官网:

https://www.muruhui.org/

分享

收藏

点赞

在看

本篇文章来源于微信公众号: 国际母乳会LLL